Democracy and Mega-Sporting Events

Ought illiberal societies be conferred hosting powers?

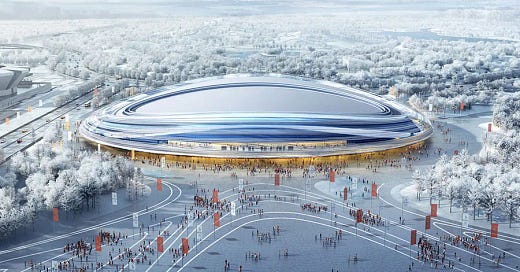

Sixteen years ago, all eyes were on China as the growing global superpower readied itself to host the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Fast forward to the 2022 Winter Olympics, once again held in the capital of the nation, criticism struck in the same area - amidst reemerging accusations of China’s sportswashing actions and calls for boycotts of the event.

An illiberal state can be defined as a governing system that deviates from what should be the obvious norms of our society and the international community, concealing its non-democratic practices behind certain institutions and procedures. Contemporary unfoldings of illiberalism can be observed in Eastern Europe - across Turkey, Hungary, Poland, et cetera. Large international sporting events may be qualified as large through the numerical size of participants, organizers, and audience. It is thus understood that with a large and international audience, these events are large not only in size, but also in influence.

Holding international sporting events in illiberal societies inevitably taints the global reputation of the event and organisation. The aforementioned 2008 Beijing Olympics faced severe criticism for providing a platform for the Chinese government despite widespread concern and claims about human rights abuses within the Republic. Condoning or supporting the involvement of illiberal societies as the hosts of such large-scale, eminent events provides symbolic endorsement of the illiberal societies and their political systems - a highly controversial and vulnerable stance for any organisation to take.

Furthermore, using illiberal states as hosting countries for sporting events compromises and undermines key sporting values fundamental to the sporting organisation and often, sports as a whole. Both the IOC and FIFA promote liberal values of political inclusion and respect for civil liberties. Political liberalization is viewed as a corollary of equality and inclusion, and the ideals espoused by both organizations are antithetical to principles recognized by illiberal societies.

That said, the commonly antipodean perspective is enshrined upon the cardinal belief within the sporting community that sports are distinct from politics, and the two should be kept separate. A state’s political alignment should not hinder its involvement, and sports should remain depoliticised. Such international events with exposure to a global audience present an opportunity to spark change in the political spheres of the host countries, ultimately bringing about a beneficial outcome. People within illiberal societies may be empowered by a heightened sense of connection to the international community to push for local reforms. In a geopolitically multi-polar and increasingly fragmented world, allowing illiberal societies to host sporting events fosters the spirit of global inclusivity - a key value within sports itself. Inclusivity can pave the way for smoother diplomacy as well, as seen in the easing of tensions during the “Ping Pong Diplomacy” between the United States and China in the 1970s, where the meeting between United States player Glenn Cowan and Zhuang Zedong of the People’s Republic of China during the World Table Tennis Championships in Nagoya opened avenues for state visits and diplomatic discussions between the two frosty nations.

Ultimately, however, the physical safety of athletes and spectators may be jeopardised in an illiberal society. Prior to the 2014 Sochi Olympics, the United States State Department had released a travel alert advising American visitors that they should have “no expectation of privacy”. Some may posit that inclusivity can be fostered with a similar outcome by only allowing citizens from illiberal states to participate in events; it would not necessarily have to entail granting illiberal states the right to hosting, which is often seen as a privilege internationally, and not worth the risk posed to all the organisations and individuals involved.