Inequality, Social Stratification, and the Mirage of Meritocracy

Are meritocracy and inequality two sides of the same coin?

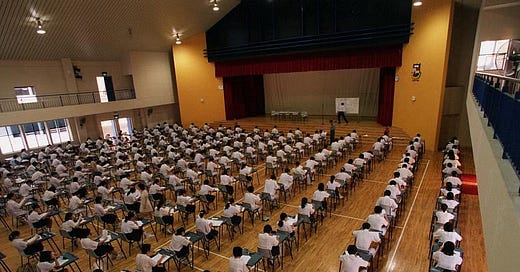

This is the narrative that Singapore assiduously propagates: in the span of a few decades, we have catapulted our economy from the post-World War II downdraft to being Asia’s economic powerhouse. We were poor, and now we are rich. We were living in attap-roofed kampung huts, and now we are living in the opulent comfort of high-rise flats. We were uneducated, and now our children top the charts in PISA rankings. We are clean, we are safe, we are phenomenal.

To maintain this phenomenality, perpetual motion is requisite. Stasis denotes failure; mobility is not merely a cosmetic factor, it is about survival. Herein lies the allure of meritocracy, a sanctified “principle of good governance”. It is this angle that deems anecdotes of poverty as dignified triumphs; a self-made entrepreneur recounts his experiences growing up in a rental flat with fondness, rather than shame, because of the assurance that he has progressed beyond those aphotic days of destitution.

This begs the question: has everyone moved up?

What about those who have, amidst Singapore’s broader trajectory of advancement as a global city, remained stagnant in their circumstances?

Top 10% versus Bottom 10%

Despite a Gini coefficient markedly surpassing that of most other nations, bolstered by empirical evidence from the Ministry of Finance indicating marginally increasing equality in recent years, inequality – manifested in a multitude of forms such as intergenerational disparities, socio-economic stratification, and consumption inequality – is a pertinent issue that Singaporean society faces.

We must also step beyond mere empirical trends, and recognize the palpable experiences of inequality and poverty in Singapore. To fail to do so is to allow for discourse devoid of humanity, insofar as we merely quote figures without naming the injustices as enacted upon real citizens. Felt experiences of a homeless student having to rise at 4 a.m. to shower at the community center before reporting to school, of a middle-aged couple struggling to accrue money in their CPF accounts to move off their Jalan Kukoh rental flat, of an airport janitor laboring for a meager 8 dollars per hour lowering their gaze out of indignity, all allow us to see the existence and deleterious impact of inequality; and once we see, we cannot, and must not unsee. It is not solely the panoptic state of inequality that warrants attention, but also the day-to-day lived realities of issues for which no amount of normative justification via meritocracy can assuage, no matter how well-entrenched the narrative.

Singapore’s Socio-Economic Fault Lines: Unraveling Unity in the Face of a Widening Class Divide

“If widening inequalities were allowed to create a rigid and stratified social system, Singapore’s politics will turn vicious, its society will fracture, and the country will wither”– Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong addressing parliament in February 2018

In 1965, the greatest divides we feared were along the fault lines of race and religion. In 2023, it’s class.

Socio-economic inequality inevitably translates into inequality in belonging; a CNA production featuring Dr. Janil Puthucheary unveiled that 76% of affluent Singaporeans experienced a sense of belonging to Singapore, whereas only 46% of the lower socioeconomic bracket expressed similar sentiments. This phenomenon can in part be ascribed to the marginalization experienced by the latter, exacerbated by their precarious economic circumstances, which in turn engender feelings of vulnerability and unease within their surroundings. Privileged individuals are endowed with heightened access to avenues for personal and vocational advancement, resulting in a more profound engagement with society, and a heightened sense of active involvement. Conversely, those grappling with the exigencies of daily survival find themselves bereft of the time required for active civic engagement. For the high socioeconomic status, the city is full of promise. For the low-income, it is a city of constrained movement – their lives are characterized by limited opportunities and a pervasive hopelessness of perpetual immobility.

In contrast to the perspective articulated by Professor Ian Holliday which posits that social policy in Singapore is subordinate to economic imperatives, it is evident that Singapore’s robust economic advancement has rested upon a stable socio-political climate, for which economic progress functions as a means, not an end. As her economic structural transformation decelerates, Singapore finds herself at a watershed juncture where challenging, yet decisive measures are imperative to safeguard the security of her social fabric, which had hitherto been upheld by ventre à terre economic growth. Inasmuch as Singapore’s policies have historically served as a subject of examination for neighboring economies, the ramifications of the policy shortcomings allowing insidious inequality to fester within Singaporean society will resonate well beyond our shores. For Singapore herself, inequality is now an issue of paramount national significance, intricately linked to the broader social compact of a functional meritocracy.

Solutions Falling Short of Equality: The Meritocratic Mirage

The promise of equality is often described as a promise of mobility. Meritocracy has long been upheld as a cornerstone of governance and social organization. However, a nuanced examination reveals that meritocracy, once venerated as the antidote to societal disparities, falls short of its proclaimed objectives. Instead of rectifying inequalities, it inadvertently fosters and perpetuates them.

Meritocracy was devised as a social leveler: operating as a mechanism for the categorization, selection, and differential rewarding of individuals. It endorses the procedural aspects and outcomes of this categorization, predominantly rooted in narrow conceptions regarding what merits acknowledgment and what does not.

In situations characterized by what Pierre Bourdieu coined as “misrecognition”, Singaporeans misconstrue the system’s operational foundation, erroneously perceiving it to be grounded in certain principles when, in actuality, it operates on an entirely different basis. Institutionalized meritocracy appears to reward each individual’s industriousness, when in reality, it perpetuates the inheritance of economic and cultural capital from one generation to the next. Meritocracy legitimizes those who emerge as its victors, portraying them as individuals who have attained success solely through their own diligent efforts and intellectual acumen, as opposed to any unearned advantages; for those who do not succeed, it is framed as a product of individual shortcomings rather than of systemic disadvantages when in reality, they are often confined within their strata by a confluence of educational credentials that do not open doors, jobs that pay poorly, intergenerational immobility and care gaps that are not adequately addressed.

Meritocracy: Falling Short of Its Promise, or Realizing Its Full Potential?

The prevailing critique of meritocracy asserts that it deviates from its intended functionality. The issue, it contends, lies not with the fundamental principles underpinning the system, but rather with its execution. Consequently, a plethora of adjustments are advocated to refine meritocracy.

There is a facet of the meritocratic framework that seldom garners attention: although the system aspires to equitable competition, the fruits of this competition inexorably yield unequal standings in terms of academic qualifications, vocations, income, and wealth. The concept of meritocracy has never been predicated on achieving, nor does it feign to produce equal outcomes. Inequality emerges as a logical consequence of the meritocratic construct.

Ergo, incrementalist approaches regarding meritocracy alone are inadequate in addressing the foundational disparities in opportunity and the felt inequality that imperils national cohesion. Rather, narratives and viewpoints must be reconfigured. State actions in tandem with corporate practices are imperative – and for actions to be taken, the issue of inequality and poverty must be brought into the limelight of policy discussions.

Shifting Paradigms: Rethinking Narratives for a Brighter Future

We must refrain from ghettoizing the problem of poverty – thinking of it as a predicament of the ‘other,’ dichotomized into benefactors and recipients of assistance. It is exigent to interlink discussions of wealth with conversations about poverty. We must understand that elitism and marginalization are two sides of the same coin. We must stop being coy in speaking about the notions of exploitation in everyday contexts, and lived experiences.

This is a moral quandary; a comprehensive examination of our systems is warranted; education, purported meritocracy, and welfare – all require profound transformations surpassing superficial, peripheral adjustments.

Inequality is not rocket science. Step one is to actively confront the issue, and disrupt the prevailing narratives.

Citations: Information and data obtained from CNA resources and documentaries, local studies and reports, books or full-length articles, and media, as well as international academic findings.

I believe what you meant to say was the Gini coefficient has been denoting mounting *equality* not inequality…?